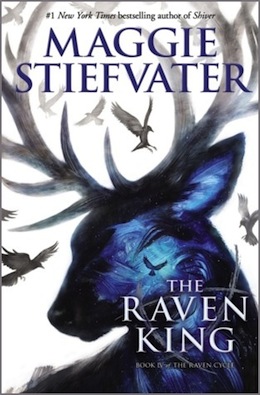

Last week saw the release of the final novel in Maggie Stiefvater’s Raven Cycle, The Raven King. While I’ll still be writing a final companion installment to the previous three-part essay on the Raven Cycle (found here)—which will be more in-depth—the pressing concern is to discuss immediate impressions.

The Raven King picks up immediately after the events of Blue Lily, Lily Blue. It’s fall, school is back in session after one perfect strange summer, and the fivesome are all facing down imminent changes in their lives. College, and the lack thereof; love, and the consequences thereof; magic, and the cost thereof. The arc has built up through three prior books to a trembling, tense point where it’s all going to come to a shattering conclusion. And with perhaps the most chilling, devastating end-of-prologue lines I’ve had the pleasure of reading, Stiefvater sets off the final book in the cycle:

The hounds of the Aglionby Hunt Club howled it that fall: away, away, away.

He was a king.

This was the year he was going to die.

That prologue—in specific, the refrain of he knew—is a concrete example of the cyclical structure and depth of implication in these novels. For the previous three, we’ve been reading under the assumption that Blue knows Gansey is going to die within the year, and then also Adam, but that no one else in the group does. However, as the prologue gives us Gansey’s point of view, it lets us know that at every moment, for every word spoken through the previous arcs, he has known he was going to die.

It changes everything; it’s breathtaking. In The Dream Thieves, when he tells Ronan, “While I’m gone, dream me the world. Something new for every night,” he knows. While I’m gone has two meanings, but only Gansey knows one of them. This is the sort of stunning, intense emotional backlogging that Stievater delivers, rewarding constant vigilance and rereading. However, this doesn’t mean that the books in the Raven Cycle aren’t fast-paced and gripping as well.

The Raven King, in particular, I sat and read in one approximately six-hour binge. (I of course have read it again, since then, but the point stands.) This review is, then, the first pass impression of the book; the essay, forthcoming, will tackle the meatier bits. Because most of you just want to know: was it good, did it end well? Should I read the series?

Yes and yes and yes.

SPOILERS AHEAD.

Stiefvater had a great big handful of threads to tie up in the closing of this cycle, and she does an admirable job with sorting them all out in a manner that feels both natural and satisfying. The disparate issues of the wider political and social world, their relationships, and the quest for Glendower as well as the dangers they’ve been outrunning so far all come together in a rich mélange at the end. This is a book about crossing over into the future—something I’ll talk about more in the long form piece—but it has a lot to say about trauma and healing, about becoming the person you’ve wanted to be. Without this confrontation of past trauma and growth into better, more whole, more healthy people, the climax wouldn’t be able to happen the way that it does.

Everyone is being a better version of themselves, thanks to each other, and it isn’t outside magic that saves them: it’s their own kinship, love and devotion. While they were relying on Glendower’s favor, ultimately it’s their relationships that matter—the relationships that provide the backbone for Ronan to create, Adam to control, Gansey to sacrifice, Blue to mirror, Noah to hold on, and our newest addition, Henry, to support. That’s a heart-stopping, intense, so-bright-it-hurts message in the end.

Really, the relationships between the entire lot of them are passionate and delightful, but there are also, of course, the romantic components. And in that corner, it’s quite clear that this is Ronan and Adam’s book as much as it’s Blue and Gansey’s—if not more. Their developing relationship is given room to sprawl, to grow heated and delicate and strong, and it’s a beautiful thing. (Also, I’d just like to thank Stiefvater, again and again, for writing Ronan Lynch. Every inch of him and his narrative speaks down into my bones. It’s a bit like staring into the sun.)

Noah’s narrative in particular was handled well, with a careful and quiet skill against the backdrop of the more dangerous, obvious, loud confrontational arc. Noah struggles to hang on to himself, to eke out just another day and another moment to be there with the people he loves until he’s needed. It’s utterly devastating: that the greatest relationships he’s been able to touch were after his death, when he’s a decaying and disintegrating thing, and that the living Noah was a vibrant, ridiculous, excitable creature none of his raven gang ever had the chance to know. The scene of his sister explaining his dream about ravens battling in the sky, and how he instigated Aglionby’s raven day, was a gentle torment. Here’s a boy who is described as a “firecracker” who got speeding tickets constantly and stood on tables. He sounds like Ronan, and suddenly their intensity of friendship makes more sense.

It makes sense that the person who makes Noah laugh, throughout the series, is Ronan. It also then makes sense that the person who he gives his life up for, who he dedicates himself to, is Gansey. His last act is to slip back in time to whisper in the young Gansey’s ear the words that set him off on the path to meeting his fivesome, to having that one summer together before Noah is gone. Since time is slippery, this is also how Gansey is put together of parts of all of them in the end. If Noah hadn’t set him on the course, he wouldn’t have met them, wouldn’t have had the opportunity for Cabeswater to sacrifice itself and piece him together from the knowledge it has of his friends.

Also, that is the most satisfying instance of a promised death shifting back to a resurrected life I’ve ever encountered in a book. Magic costs; sacrifices cost. Gansey gives himself up to stop the third sleeper and save Ronan and his remaining family—then Cabeswater, a beautiful sentient thing of Ronan’s dreaming, gives itself up for Gansey and builds his resurrected self out of the pieces of his friends. As I’ve seen pointed out elsewhere: no wonder he feels right when he meets each of them, one by one, if time is an ocean; he’s literally meeting parts of his own soul.

The one complaint I had, in the close, was that none of the epilogue reflections so much as mention Noah. While he has passed on, and I do think the cycle gives him an understated but fantastic arc, I was left feeling somewhat off-balance by his absence from the minds of his friends. Considering the importance of the “murdered/remembered” scene in the first book, the intimacy Noah had with both Blue and Ronan, I would have expected one of them to spare a thought or a moment for his passing-on. (Particularly given that he’s left scars on at least Blue—and, given that we know through second-hand narration he also went full poltergeist on Ronan in the first book, likely both of them.) It’s a small complaint, of course, but given the solid execution of the rest of the text—and how it’s one of the last feelings I’m left with in the epilogue—it does stand out.

There’s also so much happening that it can, at times, feel a bit rushed. I’ve yet to decide if that’s rushed in a positive sense, or not. The cast has grown so large that it’s impossible for them all to have the same sprawling attention as our protagonists. Nonetheless, there are at least nods in several directions to the adults and secondary characters. Compared to Blue Lily, Lily Blue, though, they’re far more absent. It both makes narrative sense and is necessary while leaving me wanting more.

Of course, I don’t think that wanting more is necessarily a failing. I appreciate the sense of possibility this book closes with, of paths still left to be taken, magic still left to be done, adventures to be had. Blue and Gansey and Henry, our fascinating fresh threesome, are off to roadtrip in their gap year; Ronan is settling in at the family farm to refinish floors and raise his orphan-girl and discover his own slow sweet happiness, recovering from loss—his father, his mother, and also Kavinsky—while Adam goes off to college. But they’re all always-already coming back to each other. It’s unshakeable, their bond, and as the women of Fox Way tell Blue early on in the story, there’s nothing wrong with leaving because it doesn’t mean never coming back.

Overall, The Raven King has a lot to recommend it. The book handles the closing of the cycle with fantastic skill, tension, and a wrap-up so complex I’ve barely scraped the surface of it here. I was not disappointed; anything but, in fact. I’ve got the pleasant ache of a feeling that I won’t be moving past this in the near future—it’s certainly one of the best series I’ve ever read, hands down, for the things it does with trauma, with love, with people being people together. I recommend picking it up and reading it twice. More, if the fancy strikes you. But certainly, do so.

The Raven King is available now from Scholastic.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.